Rugby union referee Nigel Owens reveals his struggle with eating disorder bulimia nervosa is not over and remains an ongoing battle.

There have been a number of ‘firsts’ in my life.

As a referee in world-class rugby, one of the most macho sports on the planet, I was the first in the sport to come out as being gay.

In the hope of reaching out to other young people struggling with mental health, I was also one of the first sportsmen to speak openly about the biggest regret of my life – a suicide attempt.

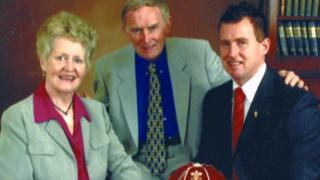

Early one morning at the age of 26, I left a note for my mum and dad, both of whom had been hugely supportive of me, explaining I couldn’t carry on, that I desperately wanted to bring it all to an end.

I took an overdose, laid down on a Welsh mountainside and waited to die. Doctors later told me I was just 20 minutes from death when I was airlifted to hospital by a police helicopter.

So I got a second chance. I was determined not to waste it and using my experience to help someone else is a pretty good way of ensuring that.

Which brings me onto another ‘first’; I’ve spoken about dealing with bulimia in the past but have never before revealed that to this day I continue to struggle with an eating disorder.

Since the age of 18, I have had bulimia nervosa.

It is a disorder of overeating followed by fasting or self-induced vomiting or purging.

It was a secret I was still battling to control as I stepped on to the pitch to referee the Rugby World Cup in 2015.

And I’m not alone.

Eating disorders have the highest death rate of any mental health illness and are estimated to affect 1.6 million people in the UK. Around 400,000 are thought to be men and boys.

And that number is growing.

The reasons vary from person to person; body image, obsessive exercise, sporting achievement and the relentless bombardment of ripped physiques on social media and so on.

When I was growing up in a small village in rural Carmarthenshire, west Wales, over 30 years ago, social media didn’t exist.

I enjoyed a happy childhood with loving, supportive parents, grandparents, uncles and aunties. I had a good time at school and loved to go fishing and, of course, play rugby.

So far, so normal.

But when I reached my late teenage years, things changed. I started to realise that I was different, that “something was wrong”.

In the world I grew up in, you get a girlfriend, you get married, you have children, become grandparents and that’s the way the world turns.

But I was finding myself attracted to men and couldn’t figure out what on earth was going on.

It was totally alien to me. I had no idea what being gay was, I’d never even met a gay person before.

Desperate not to become this person, I struggled to suppress him. I felt I was lying to my parents, the people that mattered the most to me, which went against everything I’d been taught.

I became very depressed.

Add to the burden the fact that I was overweight, about 16.5 stone (105 kg).

In my eyes I was obese and thought “no-one who I find attractive was ever going find me attractive while I’m fat”.

So, I started making myself sick.

Find out more

Panorama: Men, Boys and Eating Disorders on BBC One and BBC iPlayer 24 July 2017 at 20:30 BST

Nigel Owens: Bulimia and Me on BBC One Wales and BBC iPlayer on 24 July 2017 at 20:30 BST

Links to organisations offering support on eating disorders below or visit BBC Action Line

For help and information on eating disorders visit BBC Advice

I loved food then as much as I do now. I’d eat all I wanted then go the loo and make myself sick.

I suffered from mild colitis, a bowel condition, so would use that as an ideal excuse to friends when I had to slip off to the toilet all the time. I was lying and being sly which only exacerbated my depression.

Before long I was bringing up every meal I ate.

Over a period of four months, I’d lost five stone.

No-one suspected a thing. I was running and training a lot and my friends and family could see me scoffing food every mealtime, so as far as they were concerned I was eating well. I was training hard so outwardly I looked fit and healthy.

An eating disorder wouldn’t have crossed anyone’s mind. There wasn’t much awareness back then and if there was it was associated with young girls.

Meanwhile, I was about to get sucked even further into the vortex of self-harm and depression.

In my eyes, I was now too thin and now thought “no-one I find attractive is ever going to find me attractive while I’m skinny”.

So I went to the gym and began using steroids. I became hooked on them for the next seven, eight years.

Mental health issues, depression over my sexuality, bulimia and steroids – my life was an unrelenting nightmare.

I was broken.

I’ll never forgive myself for what I put my parents through. Imagine getting up in the morning and finding that goodbye letter, the sheer panic that they’re never going to see their son again.

But if there was any consolation from this dreadful event, it was while recovering in hospital that my life began to turn around.

I tried to come to terms with who I was, I stopped taking the steroids and tried to fight against the bulimia.

After years of struggling with an eating disorder it was when my beloved mother was diagnosed with cancer and given a year to live that I finally vowed to stop. I was 36 then. It stopped for a few years.

I never sought professional help but I took advice from a professional nutritionist and followed a food plan. I cut a lot of carbohydrates from my diet and trained differently and I was in the best shape I’d ever been in, physical and mentally.

The bulimia had stopped and I was doing the right thing to keep my weight down by eating sensibly. I would have treats but in moderation, I’m a big believer in that. Trouble can rear its head when you totally deny yourself some pleasures in life like chocolate or the odd pint of beer.

In 2015 I reached the pinnacle of my career – I refereed a World Cup Final – in a memorable match between New Zealand and Australia.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images  Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images I’m known for being a steely, authoritative and, I hope, fair referee. As I walked onto the pitch that day, no-one would have believed that I was battling the creeping return of my bulimia.

In the run up to the Rugby World Cup, I’d been under huge pressure to reach certain fitness levels – you have to reach an advanced level on the Yo-Yo Endurance Test (a variation on the bleep test used to measure physical fitness).

Fitness expectations are extremely high, particularly for somebody who was 44 years of age. Bear in mind international athletes in their prime, in their 20s, are expected to reach that level and I was expected to do the same.

I was training hard but knew that if I could only shed four to five kilos my chances of passing the fitness test would improve – I’d be carrying less weight and my body would take longer to get tired.

I remember looking at the mirror and thinking: “Damn. I could get rid of this quite quickly.”

And so the bulimia returned.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Once I’d passed the test, I resumed a good routine of fitness and nutrition and went into the Rugby World Cup in peak condition.

What an incredible honour and experience that was. I’m not blowing my own trumpet but you’re refereeing the world cup final, you’re considered the best in the world.

Not bad going for a former farm worker from west Wales eh? And a world away from the first time I’d picked up a whistle as a 16-year-old having accepted I was never going to make it as a player.

But the following year, the pressure was off and I notice I was putting on weight and so the bulimia returned.

It might have been twice a week then nothing for months and months. I know it does more harm than good so why do I still do it from time to time? I don’t know.

But what I do know is that unless I control what I eat and I’m sensible about it, there’s going to come a time when I’m going to put on weight and I’m going to end up making myself sick again.

So I do everything I can to prevent getting to that stage.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images  Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images For those who are caught up in eating disorders and say there’s nothing they can do about it, I understand what they are saying because it takes you over and you feel there is nothing you can do.

But I would urge anyone suffering to do something – seek professional advice, tell people about it, don’t hide it, don’t lie about it, that’s a great first step.

I thought I was in control but since making the Panorama programme, I’ve realised I’m not.

I came back from refereeing the England summer tour in Argentina a few weeks ago. While I was out there, I made myself sick three to four times – I think because I was eating more food than I needed.

It’s been a reality check. Speaking to experts I acknowledge now that I need to do something, to sit down and speak to someone and try and get this out of my life forever.

People who’ve never had an eating disorder can try to imagine what it’s like but they will never know.

It’s not as bad as 30 years ago but even today there’s an attitude towards conditions like anorexia of ‘oh for God’s sake, don’t be silly, eat some food!’. If only it was that easy.

After all I’ve experienced in my life and having to deal with the pressure out in the field of making split-second decisions in front of millions of people, you would think I’d be strong enough to stop my bulimia.

I’m speaking openly about it because I know that men and boys can view it as a sign of weakness by admitting there’s a problem that you can’t sort out yourself.

But it’s not a sign of weakness; it’s a sign of great strength to do that.

On the programme I speak to professional boxer Bradley Pryce who made himself in the past sick to lose weight. You see these guys in the ring and think they embody mental toughness and physical strength.

It goes to show that everybody can suffer from it – a world cup rugby referee, young teenage boys and professional boxers.

If men can find it within themselves to open up about their own experiences of eating disorders, you would find them in all walks of life and in every sport in the world.

Image copyright Respect the ref campaign

Image copyright Respect the ref campaign One of the experts I’ve spoken to highlights how much body image has changed for men. A generation ago manliness would have been seen as being good at sport, providing for the family. Now there’s so much more emphasis on being muscular, having a ripped body with a six-pack.

And if you don’t have a six-pack you’re not going to be happy and no-one’s going to like you. That’s complete rubbish. And for the majority of us this is a totally unrealistic expectation.

So the more men do open up and talk about eating disorders, then the easier it’s going be to bust the stigma that this is only a female problem and, more importantly, raise awareness of the help needed to tackle this and ensure the funding is in place to provide it.

As for me, I’m focusing on passing the fitness test for the 2019 world cup. What the challenges will be when I finish refereeing and I won’t have to train for something specific, I really don’t know.

But one thing I absolutely do know is that the bulimia can’t carry on. And I just hope that by speaking about my experience I can help many others reach the same conclusion.

It’s not always easy to get the help you need when you need it so the sooner you start talking to people the better.

Don’t be in my situation; 27 years on and still suffering from it.

Read more here: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk